Post 36. Dignity Low, Head Held High

Temporary tools helped my body. A decision helped my mind.

By the time I was up and walking again in hospital, I’d already made a decision: I wasn’t going to go through life looking at the floor.

That choice might sound small, but it became a powerful statement of intent. It shaped how I carried myself—literally and figuratively—through the long recovery ahead.

I also decided I’d stare people out when passing them in the hospital corridor or on the street. How dare they look at me, I thought. Do they not know what I’ve been through? I took small victories each time I “won” by making them look away first—but over time, I realised this approach was toughening me up in the wrong way. Most people weren’t looking down at me—they were just curious.

One day, walking through the corridor to an appointment, I caught eye contact with a woman. Instead of fixing a hard stare, I smiled—and her reaction changed everything.

In that moment, I realised that most people who looked at me weren’t judging me. They were wondering how I was coping, maybe even quietly willing me on. Sure, there were some pitying looks, but I’d already decided that pity was a currency I wasn’t going to accept. That smile, simple as it was, allowed them to see I was okay—and gave them permission to be okay too.

It was the first time I really understood the power we have to shape our interactions. I stopped thinking others should be the ones to make the first move—after all, look at me!—and started to see how it was actually up to me to put them at ease. Making eye contact, offering a smile, maybe even throwing in a bit of quick wit—that proactive approach became a new life superpower.

Even with my head held high, I still needed support—literally. I wore one, two, sometimes three clear rubber tubes around my neck to stop scar tissue from tightening and pulling my head downward. They were surprisingly easy to get used to, and I’d often forget they were even there until one would pop off.

Same with the pressure garments—custom-made pieces of elasticated fabric, tailored to hug my limbs, hands and lower back with constant compression. Designed to stop my scar tissue from rising and thickening too much, they became part of my daily uniform. I don’t even remember feeling too hot wearing them during the summers of 1993 and 1994. My memory on all this could be a bit off—but if it is, I’m glad I’ve been left with more positive memories.

Mum remembers the routine well. After carefully applying moisturising cream to all my scars (a morning and nighttime occurrence), she’d lift my frail frame—I was down to 4.5 stone at one point—with one arm and dress me with the other, just like when I was a toddler.

But not all the additions were so easy to ignore.

Not totally accurate but the closest images I could find to help you visualise what was fitted to me.

One of the worst offenders (aside from the face splint, which I’ll get into next week) was the mouthpiece—an awkward, laterally-sprung contraption that stretched out both sides of my mouth. I’d talk funny with it in, dribble constantly, and disliked how it made me feel. But I could feel the corners of my mouth tightening without it, and deep down I knew it mattered.

Before I got to this stage, though, it was my care assistant Eddie—back in Dublin—who first got me used to having splints in my mouth. Each day, Eddie would insert a new wooden wedge between my teeth, gradually stretching them bit by bit to maintain as much access and flexibility as possible. It wasn’t pleasant, and my only defence was to try and kick him in the head—a move he was already wise to.

I remember one Sunday, wearing the mouthpiece while speaking to my maternal Granny and Grandad on the phone. They never got to see me again after the accident—they both passed away within three years. It was decided they were better off not knowing how badly I was injured. I’m not sure how I feel about that now. I think they were more resilient than they were given credit for maybe.

The hardest aids to manage, though, were the ones for my hands.

Finger splints, held in place with surgical tape, were sometimes placed over skin that hadn’t fully healed. They were there to keep my fingers as straight as possible, but they made my hands less functional and were pretty painful at times. What made them harder still was knowing they were trying to undo damage from an earlier operation in Dublin—an extra layer of frustration on top of the pain.

And then there was the CPM (continuous passive motion) machine.

This thing became like an extra limb. It mimicked my physiotherapist Claire’s work, stretching my fingers back and forth to prevent scar tissue and tendons from tightening. I had to use it two or three times a day—while watching telly, in the car, even on holidays. My parents, siblings, and close family friends were all enlisted to make sure I wore it. I wasn’t always up for it, but I know now how much it mattered for the success of huge upcoming operations. The 20% of function I now have in my right hand probably wouldn’t exist without it.

There’s one funny story from that time. One of our closest family friends, Eileen (pictured), was looking after me and had instructions to fit the machine to my right hand. By then, my dog Ricki (pictured twice) had gone from being nervous around me to becoming my fiercest protector. When he saw Eileen trying to attach this alien-looking contraption to me, he went for her! We’d never seen him do that before—it shocked us all. We calmed him down quickly, and though it sounds less funny now, we laughed about it often back then. I guess any kind of humour was seized upon in those days, a welcome way to lighten the mood.

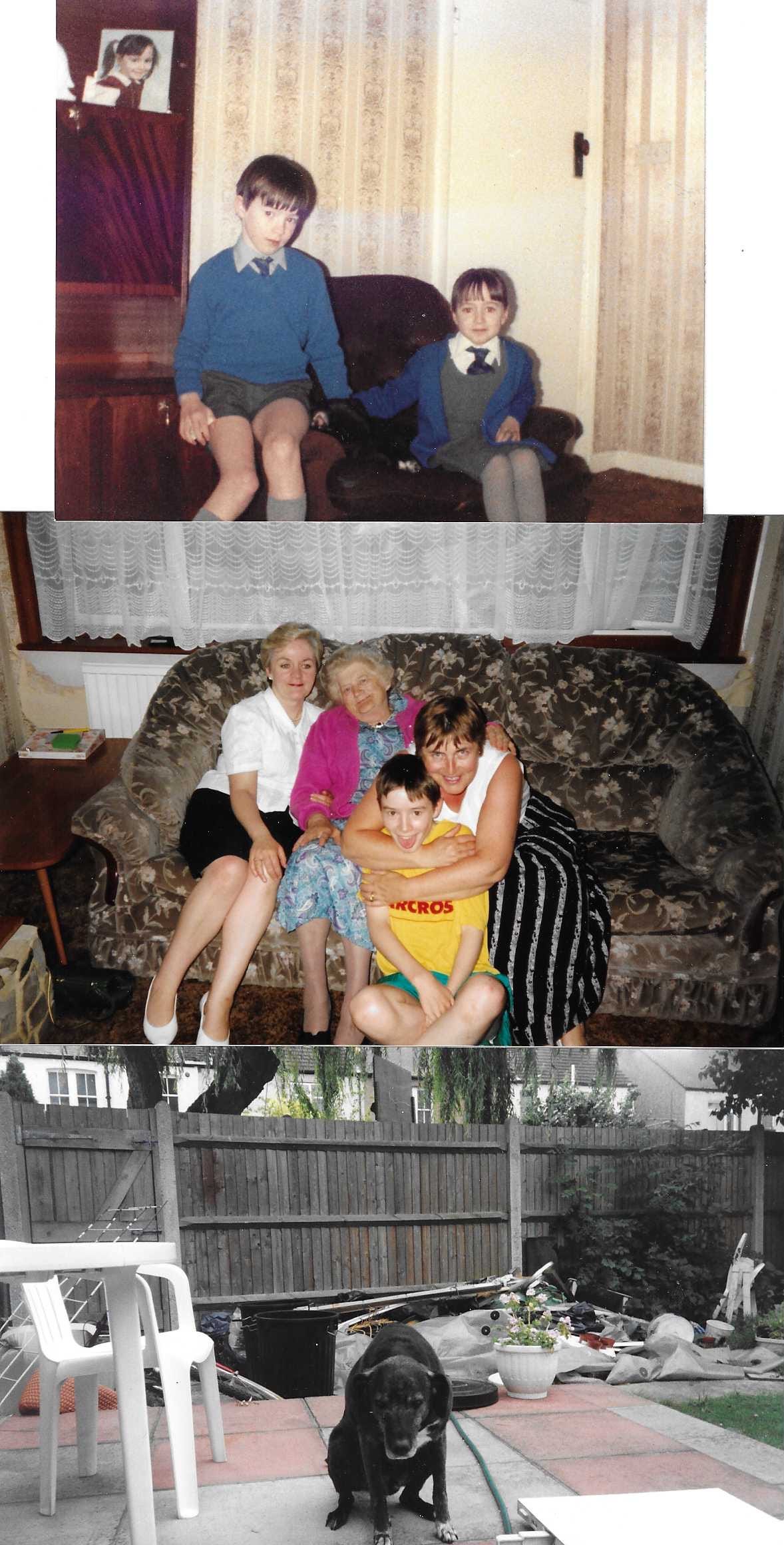

Top: Caroline and I with a young and rarely calm, Ricki.

Middle: Eileen (pictured with her and my mum grabbing me on the very same sofa Ricki would go for her a year or so later).

Bottom: Old boy Ricki nearing the end of being a one of a kind and most loyal dog.

These additions—these extras—were all temporary. I’ve often described my five-year recovery journey as one of survival, working to regain dignity and independence. We could tick off survival, were a long way from independence, and firmly in the thick of having very little dignity. From being sliced open every few days to needing help wiping your bum, I had to almost detach from ownership of my body just to cope.

But each addition helped me inch forward—stretch, soften, reshape. My body had to be broken down in order to heal stronger. And as it did, I regained dignity step by step. My mindset had to do the same.

But the most important decision I made wasn’t fitting one more splint or enduring one more piece of plastic around my neck.

It was choosing, every day, to walk with my head held high.

Next week: the face splint.

Hi great chapter. I remember all to well the " lollies pop" sticks I placed between your teeth.

I felt ur pain pal, and often dripped a tear from my eyes later thinking, how could I hurt this kid.

I had to kick myself up the backside, and say he needs this.

Wasn't easy but, hey, so glad I did it.

One extra splint every day, one new explicit from you. Ha ha 😂

Keep going my friend, I am as proud of you now as I was back then.

Eddie

Always head held high Marc!

So proud of you, so grateful to Eddie Barry and all the many Eddies over the years.